In what form is the theme of the variation written? Artistic and educational value of variational music-making in the process of formation of the variational form. Johann Sebastian Bach. Goldberg variations

Period Complications

Russian folk song

Simple two-part form

three-part form

Complicated three-part shape

Theme with variations

Rondo

sonata form

Rondo Sonata

Cyclic forms

mixed forms

Vocal forms

A theme with variations is a form consisting of the original presentation of the theme and several repetitions of it in a modified form, called variations. Since the number of variations is not limited, the scheme of this form can only have a very general form:

A + A 1 + A 2 + A 3 …..

The method of varied repetition has already been encountered in relation to the period, as well as to two- and three-part forms. But, manifesting itself there in the repetition of some part or in the methods of thematic work, it carries, in a certain sense, an auxiliary, auxiliary role, even with the dynamization that it introduces. In the variational form, the method of variation1 plays the role of the basis of shaping, since without it a simple repetition of the theme in a row would result, which is not perceived as a development, especially in instrumental music.

In view of the fact that the oldest examples of variations are directly related to dance music, it can be assumed that it was it that served as the direct source and reason for the emergence of the variation form. In this regard, its origin, although perhaps not direct, from folk music is quite likely.

Variations on basso ostinato

In the 17th century, variations appeared, built on the continuous repetition of the same melodic turn in the bass. Such a bass, consisting of multiple repetitions of one melodic figure, is called basso ostinato (stubborn bass). The initial connection of this technique with the dance is shown in the titles of the pieces constructed in this way - the passacaglia and the chaconne. Both - slow dancing in tripartite size. It is difficult to establish a musical distinction between these dances. At a later time, the connection with the original three-part meter is sometimes even lost (see Handel, Passacaglia in g-moll for the clavier), and the old names of the dances indicate only the genus of the variational form. The dance origin of the passacaglia and chaconne is reflected in the structure of the theme, which is a sentence or period of 4 or 8 bars. In some cases, variations of the described species do not have a name indicating their structure.

As already mentioned, the ostinato melody, as a rule, is repeated in the bass; but sometimes it is temporarily transferred, for a change, to the upper or middle voice, and also subjected to some ornamentation (see Bach Passacaglia in c-moll for organ)

If the ostinato bass remains unchanged, the variational development falls on the pre / but upper voices Firstly, in different variations a different number of them is possible, giving one or another degree of concentration of harmonies, which can be adjusted in order to increase interest Secondly, with an unchanged bass, melody at least one upper voice must change in order to overcome monotony. Consequently, the ratio of some extreme voices is already to some extent polyphonic. Other voices also often develop, polyphonizing the entire musical fabric. Variety can be created by different degrees and types of general movement. This is directly related to the distribution of movements over larger or smaller durations. In general, a gradual increase in the saturation of music with various kinds of movement, melodic-polyphonic and rhythmic, is typical. In the large cycles of variations on the basso ostinato, a temporary rarefaction of the texture is also introduced, as if for a new run.

The harmonic structure of variations on the basso ostinato in each cycle is more or less homogeneous, since the unchanging foundation of harmony - the bass - allows a limited number of variations in harmony. Cadenzas are found predominantly in full at the end of repeated figures; sometimes the dominant of the last measure of a figure forms, together with the initial tonic of the next similar figure, an invading cadenza. This technique, of course, creates greater fusion and coherence, contributing to the integrity of the whole form. On the verge of two variations, interrupted cadenzas are also possible (see “Crucifixus” from Bach’s Mass in h-moll ).

The structure of the variations, due to the repetition of the ostinato four- or eight-measure bar, is generally uniform, and a certain masking of the periodicity is possible only on the basis of the invading cadences mentioned above, as well as with the help of polyphonic overlays of ends and beginnings. The latter is relatively rare. Above all, the brevity of the parts of the form itself serves as a driving force, they are so small that they cannot be presented as independent.

Variations on basso ostinato, originating around early XVII century, became widespread towards its end and in the first half of the 18th century. After that, they give way to freer forms of variation and are quite rare. Late samples: to a certain extent - Beethoven. 32 variations; Brahms Fourth Symphony, finale; Shostakovich Eighth Symphony, part IV. Limited usage occurs from time to time, for example, in the coda of the first movement of Beethoven's ninth symphony, in the coda of the first movement of Tchaikovsky's sixth symphony. In both these works, ostinato does not have an independent meaning, and its use in conclusions resembles a tonic organ point. Nevertheless, one can occasionally come across independent pieces based on ostinato. Examples: Arensky. Basso ostinato, Taneyev Largo from piano quintet, op. thirty.

Strict variations. Their theme

In the 18th century, partly in parallel with the existence of basso ostinato, but especially towards the end of the century, a new type of variation form was formed - strict (classical) variations, sometimes called ornamental. Their prototype can be seen in following one of the dances of an old suite of variations on it, provided with numerous small decorations, without any significant changes in all the main elements (the so-called Doubles). The techniques developed in ostinato variations also left their mark on the formation of a new type of variational form. Separate features of continuity will be shown below.

First of all, both continuity and new features are already evident in the theme itself.

On the melodic side, the theme is simple, easily recognizable, and contains typical phrases. At the same time, there are no too individualized turns, since they are more difficult to vary, and their repetition would be annoying. The contrasts are slight, but there are elements that can be developed on their own. The pace of the theme is moderate, which, on the one hand, favors its memorization, on the other hand, it makes it possible to speed up or slow down in variations.

On the harmonic side, the theme is tonally closed, internal structure its typical and simple, as well as the melody. The texture also does not contain any complex figurative harmonic or melodic patterns.

In the structure of the topic, its length is primarily important. Already in Bach's time, there are themes in a simple two-part form, along with short themes. For the theme of classical variations, the two-part form with a reprise is most characteristic; less common tripartite.

The latter, apparently, is less favorable for the variational form, since on the verge of each two variations, in this case, there are parts of the same length, with a similar content:

Especially rare is a theme consisting of one period. Such an example is the theme of Beethoven's 32 variations, which, however, resemble the old variations on ostinato, in particular, in the structure of the theme. In the structure of two-part themes, small deviations from squareness are not uncommon.

Examples: Mozart. Variations from the piano sonatas A-dur (extension of period II); Beethoven. Sonata, op. 26, part I (expansion of the middle).

Variation Methods

Orn "a mental variation as a whole gives a more or less constant proximity to the topic. It, as it were, reveals different sides of the topic, without significantly changing its individuality. Such an approach, as if from the outside, can be characterized as objective.

Specifically, the main modes of variation are as follows:

1) Melody (sometimes bass) is subjected to figurative processing. Of great importance is the melodic figuration - processing by auxiliary, passing and detentions. The reference sounds of the melody remain in their places or are pushed to another nearby beat of the measure, sometimes they are transferred to another octave or another voice. Harmonic figuration in melody processing

is of somewhat lesser importance. The melody, in original or modified form, can be placed in another voice.

Rhythmic changes, mainly acceleration of movement, are directly connected with the figuration of the melody. Sometimes the meter also changes. Most of these techniques can be found already in the music of the first half of XVIII century (see Bach's Goldberg Variations). The tradition of polyphonization of at least some parts in the variational cycles of that time was also reflected in the ornamental variations of the classics. Some variations in their cycles are entirely or partially built canonically (see Beethoven, 33 Variations). There are whole fugues (see Beethoven, Variations, op. 35) and fughettas.

2) Harmony, in general, changes little and is often the most recognizable element, especially with wide figurations in a melody.

The general plan, as a rule, is unchanged. In the details one can find new harmonies formed from figurative changes in voices, sometimes new deviations, an increase in chromaticity.

Variation in harmonic figuration accompaniment is very common.

The tonality throughout the entire cycle of variations remains the same. But, partly in early XVIII centuries, and in the variations of the classics all the time, modal contrast is introduced. In small cycles, one, and sometimes in large ones, several variations are composed in a key of the same name to the main one (minor in major cycles, maggiore in minor ones). In these variations, changes in the chord are relatively common.

3) The form of the theme before the classics and with them, as a rule, does not change at all or almost, which, in turn, contributes to its recognition. Deviations from the form of the theme are most common for those variations in which the main role is played by polyphonic elements. Fugues or fughettas that occur as variations, based on the motives of a theme, are built according to their own rules and laws, regardless of its form (see Beethoven. Variations, op. 35 and op. 120).

So, many methods of variation invented in pre-classical art were accepted by the classics, and, moreover, significantly developed by them. But they also introduced new techniques that improved the variational form:

1) Some contrast is introduced within individual variations.

2) Variations, to a greater extent than before, contrast in character with each other.

3) The contrast of tempos becomes common (in particular, Mozart introduced a slow penultimate variation into the cycles).

4) The last (final) variation is somewhat reminiscent in character of the final parts of other cycles (with its new tempo, meter, etc.).

5) Codes are introduced, the extent of which partly depends on overall length cycle. In the coda there are additional variations (without number), sometimes developmental moments, but, in particular, the techniques usual for the final presentation (additional cadenzas). The generalizing meaning of the coda often manifests itself in the appearance of turns close to the theme (see Beethoven. Sonata, op. 26, part I), individual variations (see Beethoven. 6 variations in G-dur); sometimes, instead of a coda, the theme is carried out in full (see Beethoven. Sonata, op. 109, part III). In preclassic times, there was a repetition of the Da Capo theme in the passacaglia.

Order of Variations

Separation and isolation of the parts of the variational cycle gives rise to the danger of fragmentation of the form into isolated units. Already in the early samples of variations, there is a desire to overcome such a danger by combining variations into groups according to some sign. The longer the whole cycle, the more necessary is the enlargement of the general contours of the form, through the grouping of variations. In general, in each variation, any one method of variation dominates, without completely excluding the use of others.

Often a number of neighboring variations, differing in details, have a similar character. Especially common is the accumulation of movement through the introduction of smaller durations. But the larger the whole form, the less the possibility of a single continuous line of ascent to the maximum of movement. First, an obstacle to this is the limited possibilities of motor activity; secondly, the final monotony that would inevitably result from this. A design that gives rise, alternating with recessions, is more expedient. After a fall, a new rise may give a higher point than the previous one (see Beethoven, Variations in G-dur on an original theme).

An example of strict (ornamental) variations

An example of ornamental variations, with very high artistic merit, is the first movement of the piano sonata, op. 26, by Beethoven. (To save space, nz theme and all variations, except for the fifth, one first sentence is given.) The theme, built in the usual two-part form with a reprise, has a calm, balanced character with some contrast, in the form of delays sf on a number of melodic peaks. The presentation is full-sounding in most of the topic. Register favoring cantilena:

In the first variation, the harmonic basis of the theme is completely preserved, but the low register gives a thicker sound and a “gloomy” character to the beginnings of sentences I and II, the end of sentence I, and the beginning of the reprise. The melody in these mouth sentences is in a low register, but then moves out of it into a lighter area. The sounds of the melody of the theme are partly shifted to other beats, partly transferred to other octaves and even to a different voice. Harmonic figuration plays an important part in the processing of the melody, which is the reason for the new placement of the melody sounds. The rhythm predominates, as if running

hit an obstacle. In the first sentence of the second period, the rhythms are more even, smoother, after which the main rhythmic figure returns in the reprise:

In the second variation, also while maintaining the harmony of the theme, the changes in texture are very distinct. The melody is placed partly in the bass (in the first two measures and in the reprise), but already from the third measure in the broken intervals of the bass, a second, lying above it, middle voice is outlined, into which the theme passes. From the fifth measure, the wide jumps in the left hand quite distinctly stratify vote. The melody of the theme is changed here very little, much less than in the first variation. But, in contrast to the theme, the new texture gives the second variation the character of excitement. The movement in the part of the left hand is almost entirely sixteenth, in general, with accompaniment voices of the right hand, thirty-second. If the latter in the first variation seemed to “run into an obstacle”, then here they flow in a stream, interrupted only with the end of the first period:

The third variation is minore, with a characteristic modal contrast. This variation contains the greatest changes. The melody, previously undulating, is now dominated by an upward movement in seconds, again with overcoming obstacles, this time in the form of syncopation, especially at the moments of detention. At the beginning of the middle, there is a more even and calm movement, while its end is rhythmically close to the upcoming reprise, which is completely similar to the second sentence of the first period. The harmonic plan is significantly changed, except for the four main cadences. Changes in the chord are partly due to the requirements of the ascending line, as if pushed by the bass, which comes in the same direction (the basis of harmony here is parallel sixth chords, sometimes somewhat complicated). The register is low and medium, mainly with low basses. In general, the color of gloom and depression prevails:

In the fourth variation, the main major key returns. The contrast of the mode is also enhanced by the enlightenment of the register (mainly the middle and upper ones). The melody jumps continuously from one octave to another, followed by a Staccato accompaniment, combined with melody jumps and syncopations, gives the variation a scherzando character. The appearance of sixteenths in the second sentences of both periods makes this character somewhat sharper. The harmony is partly simplified, probably for the sake of the main rhythmic figure, but partly more chromatic, which, with the elements described above, contributes to the effect of some whimsicality. A few revolutions are given in a low register, as a reminiscence from the previous variations:

The fifth variation, after the scherzo fourth, gives the second wave of the movement's growth. Already her first sentence begins in triplet sixteenths; from the second sentence to its end, the movement is thirty-second. At the same time, in general, despite the denser movement, it is the lightest in color, since the low register is used in it to a limited extent. The fifth variation is no less close to the theme than the second one, because the harmonic plan of the theme is fully restored in it. Here, in the second sentences of both periods, the melody of the theme is reproduced almost literally in the middle voice (right hand), in 6 measures of the middle - in the upper voice. In the very first sentences, it is slightly disguised: in tt. 1-8 in the upper voice, her sounds are drawn to the end of each triplet; in bars 17-20, the two upper voices of the theme are made lower, and the bass of this place of the theme is located above them and figures:

Techniques of end-to-end development in variational form

The general trend of mature classicism towards a wide through development of form has already been repeatedly mentioned. This trend, which led to the improvement and expansion of many forms, was also reflected in the variational form. The importance of the grouping of variations for enlarging the contours of the form, despite its natural dissection, has also been noted above. But, thanks to the isolation of each individual variation, the general predominance of the main key, the form as a whole is somewhat static. Beethoven for the first time in a very large variational form, in addition to the previously known means of constructing such a form, introduces significant segments of an unstable developmental order, connecting parts, uses the openness of individual variations and the implementation of a number of variations in subordinate keys. It was thanks to the techniques new to the variational cycle that it became possible to construct such a large form of this kind as the finale of Beethoven's third symphony, the plan of which is given (the numbers indicate the number of measures).

1-11 - Brilliant swift introduction (introduction).

12— 43— Theme A in two-part form, set out in a very primitive way (actually, only the contours of the bass); Es-dur.

44-59-I variation; theme A in middle voice, counterpoint in eighths; Es-dur.

60-76-II variation, theme A in the upper voice, counterpoint in triplets; Es major

76-107-111 variation; theme A in bass, above it melody B, counterpoint in sixteenths; Es-dur.

107—116—Linking part with modulation; Es-dur - c-moll.

117-174-IV variation; free, like fugato; c-moll - As-dur, transition to h-moll

175-210 - V variation; theme B in upper voice, part with fast counterpoint in sixteenths, later in triplets; h-moll, D-dur, g-moll.

211-255 - VI variation; theme A in the bass, above it a completely new counter-theme (dotted rhythm); g-moll.

256-348 - VII variation; as if development, themes A and B, part 3 of the appeal, the contrapuntal texture, the main climax, C-dur, c-moll, Es-dur.

349-380 - VIII variation; theme B is carried extensively in Andante; Es-dur.

381-403-IX variation; continuation and development of the previous variation; theme B in bass, counterpoint in sixteenths Transition to As-dur.

404-419 - X variation; theme B in the upper voice, with a free continuation; As-dur transition to g-moll.

420-430-XI variation; theme B in the upper voices; g-moll.

429-471 - A coda introduced by an introduction similar to that which was at the very beginning.

Free variations

In the 19th century, along with many examples of the variational form, which clearly reflect the continuity of the main methods of variation, a new type of this form appears. Already in Beethoven's variations, op. 34, there are a number of innovations. Only the theme and the last variation are in the main key; the rest are all in subordinate keys arranged in descending thirds. Further, although the harmonic contours and the main melodic pattern in them are still little changed, the rhythm, meter and tempo are changing, and moreover, in such a way that each variation is given an independent character. ![]()

In the future, the direction outlined in these variations received significant development. Its main features:

1) The theme or its elements are changed in such a way that each variation is given an individual, very independent character. This approach to the treatment of the theme can be defined as more subjective than that which was manifested by the classics. Programmatic meaning begins to be given to variations.

2) Due to the independence of the nature of the variations, the whole cycle turns into something similar to a suite (see § 144). Sometimes there are links between variations.

3) The possibility of changing keys within a cycle, outlined by Beethoven, turned out to be very appropriate for emphasizing the independence of variations through a difference in tonal color.

4) Variations of the cycle, in a number of respects, are built quite independently of the structure of the theme:

a) tonal relationships within the variation change;

b) new harmonies are introduced, often completely changing the color of the theme;

c) the theme is given a different form;

d) variations are so far removed from the melodic-rhythmic pattern of the theme that they are pieces that are only built on its individual motifs, developed in a completely different way.

All of the above features are, of course, various works XIX-XX centuries are manifested in different ways.

An example of free variations, of which some retain a significant proximity to the theme, and some, on the contrary, move away from it, can serve as Schumann's Symphonic Etudes, op. 13, written in variational form.

"Symphonic Etudes" by Schumann

Their general structure is as follows:

The theme of the funeral character of cis-moll is in the usual simple two-part form with a reprise and with a somewhat contrasting smoother middle. The final cadenza, quite “ready” for completion, however, turns towards the dominant, which is why the theme remains open and ends as if interrogatively.

I variation (I etude) has a march-like, but more lively character, becoming smoother towards the end of the middle. The new motif, carried out at first imitatively, is “embedded” in the first sentence in the harmonic plan of the theme. In the second sentence, he counterpoints the theme held in the upper voice. The first period, which ended in the theme with modulation into parallel major, does not modulate here; but in the middle of the form there is a new, very fresh deviation in G-dur. In the reprise, the connection with the theme is again clear.

II variation (II study) is built differently. The theme in the first sentence is carried out in bass, the upper voice is entrusted with a new counterpoint, which remains alone in the second sentence, replacing the theme and obeying, basically, its harmonic plan (the same modulation in E-dur).

In the middle, the melody of the theme is often carried out in the middle voice, but in the reprise, a slightly modified counterpoint from the first period remains, while maintaining the harmonic plan of the theme, in its main features.

III etude, not called a variation, has a distant theme with the theme.

connection. The tonality of E-dur, which was previously subordinate, predominates. In the second measure of the melody of the middle voice, there is an intonation corresponding to the same intonation of the theme in the same measure (VI-V). Further, the direction of the melody only approximately resembles the figure TT. 3-4 topics (in the topic fis-gis-e-fis in the etude e-) is-efts-K). The middle of the form approximately corresponds to the middle of the theme in the harmonic plan. The form became three-part with a small middle.

III variation (IV etude) is a canon, which is built on the melodic pattern of the theme, somewhat modified, probably for the sake of imitation. The harmonic plan is somewhat changed, but its general outlines, like the form, remain close to the theme. Rhythm and tempo give this variation a decisive character.

Variation IV (V etude) is a very lively Scherzino, proceeding mainly in light sounds with a new rhythmic figure. Elements of the theme are visible in the melodic contours, but the harmonic plan is much less changed, only both periods end in E-dur. The form is two-part.

V variation (VI etude) is both melodically and harmonically very close to the theme. The character of excitement is given not only by the general movement of thirty-seconds, but also by syncopated accents in the part of the left hand, despite the even movement of the upper voice by eighths. The form of the theme is again not changed.

Variation VI (Study VII) gives a great distance from the theme. Its main key is once again E-dur. In the first two measures in the upper voice there are topical sounds, as at the beginning of the theme. In tt. 13-14, 16-17 the first figure of the theme is held in quarters. This, in fact, limits the connection with the original source. The form is tripartite.

Variation VII (Etude VIII) is an approximation to the theme in the harmony of the first period and a number of new deviations in the second. The extreme points of both periods coincide with the same places of the theme. The form is still two-part, but the periods have become nine-bar. Thanks to the dotted rhythm, the graceful sixty-fourths in imitations and the incessant accentuation, the character of decisiveness is re-created. The jumps add an element of capriccioso.

Etude IX, not called a variation, is a kind of fantastic scherzo. Its connection with the theme is small (see notes 1, 4, 6 and 8 in the opening melody). The general is in the tonal plan (I period cis - E, middle cis - E, reprise E - cis). The form is a simple three-part with a very large coda of 39 bars.

VIII variation (X etude) is much closer to the theme. Not only the main features of its harmonic plan have been preserved, but also many sounds of the melody on strong and relatively strong beats have remained untouched. Auxiliaries in the upper voice, appearing in the melody, are accompanied by auxiliary chords on the fourth sixteenth of almost every beat. The rhythm resulting from this, combined with the uninterrupted common sixteenth notes, determines the energetic character of the variation. The theme has been saved.

IX variation is written in a key that was not touched before (gis-moll). This is a duet, mostly of an imitation warehouse, with accompaniment. In terms of rhythm and melodic outlines, it is the softest (almost plaintive) of all. Many features of the melody and harmony of the theme are preserved. Little changed by extensions and the form of the theme. For the first time, an introductory subcycle was introduced. General character and final

morendo contrast sharply with the upcoming finale.

Progress from the funeral theme through various variations, sometimes close to the theme, sometimes moving away from it, but mainly mobile, decisive and not repeating the main mood of the theme, lead to a light, brilliant rondofial.

The ending is only vaguely reminiscent of the theme. The chord warehouse of the melody in the first motive of his main topic, the two-part form of this theme, the introduction in the episodes between its appearances of the first melodic figure, which opens the "Symphonic etudes" - this, in fact, is how the finale is connected with the theme on which the whole work is based.

A new type of variation introduced by M. Glinka

The couplet structure of the Russian folk song served as the primary source of a new type of variational form, which was introduced by M. I. Glinka, and became widely used in Russian literature, mainly in opera songs of a song nature.

Just as the main melody of a song is repeated in each verse at all or almost unchanged, in this kind of variation the melody of the theme also does not change at all or almost. This technique is often called soprano ostinato, since there really is something in common between it and the old "stubborn" bass.

At the same time, the variation of undertones in folk music, being somewhat related to the ornamentation of classical variations, gives impetus to the addition of contrapuntal voices to the ostinato melody.

Finally, the achievements of the Romantic era in the field of harmonic variation, in turn, were inevitably reflected in a new type of variation, being especially appropriate in a variation form with an unchanged melody.

Thus, in the new variety of variational form created by Glinka, a number of features are combined that are characteristic of both Russian folk art, and pan-European compositional technique. The combination of these elements turned out to be extremely organic, which is explained not only by the talent of Glinka and his followers, but also, probably, by the commonality of some methods of presentation (in particular, variation) among many peoples of Europe.

"Persian Choir" Glinka

An example of Glinka's type of variation is the "Persian Choir" from the opera "Ruslan and Lyudmila", associated with images of the fabulous East (in examples 129-134, only the first sentence of the period is written out).

The theme of variations, which is given a two-part form with a repetition of the middle and a reprise, is stated extremely simply, with inactive harmony, part (in the first conducting of the middle) - without chords at all Deliberate monotony, with a tonal contrast E—Cis—E—and slight dynamization, by means of underlining vertices h in the reprise:

The first variation is given a more transparent character. Low basses are absent, the accompaniment pattern, which is in the middle and high registers of wooden instruments, is very light. The harmonies change more frequently than in the theme, but are diatonic to almost the same degree. More colorful harmonies appear, mostly of a subdominant function. There is a tonic organ point (Fag.):

In the second variation, against the background of an approximately equally transparent harmonic accompaniment (there are relatively low basses, but also chords above them - pizzicato), a chromatic flute ornament appears, mainly in a high register. This pattern has an oriental character. In addition to flute counterpoint, cellos are introduced with a simple melody moving more slowly (the role of the cello voice is partly orchestral pedalization):

The third variation contains significant changes in harmony and texture. The E-dur parts of the theme are harmonized in cis-tnoll. In turn, the cis-moll "mu part of the theme, to some extent, is given the harmony of E-dur (the first two of the parallel sixth chords of this part). The melody of the choir is doubled by a clarinet, which has not yet performed with a leading voice. Quite low basses with a triplet figuration, mainly with auxiliary sounds in the eastern genus, are mostly set out on the organ point. The harmony is slightly colored in the extreme parts by the major subdominant:

The fourth variation, which goes directly into the coda, approaches the theme in texture, which is very reminiscent of the general traditions of the form. In particular, low basses are again introduced, the sonority of the strings prevails. The difference from the theme is some imitation and chromatization of the harmony of the extreme parts of the theme, greater than in previous variations:

The harmonies are not polyphonic, the plagal cadences are somewhat chromatized, as it was in the third variation. All extreme parts of the theme and variations ended in the tonic. This property of the reprise itself easily gives a final character, emphasized by the repetition of its last two-bar, as an addition. This is followed by another plagal cadenza pianissimo.

In general, the "Persian Choir", which opens the third act of the opera (taking place in the magic castle of Naina), gives the impression of luxury and immobility of the fabulous East, fascination and is very important on the stage from the side of the color it creates.

A more complex example of variations, generally close to this type, is Finn's Ballad from the opera Ruslan and Lyudmila. Its difference is a deviation from ostinato in some variations and the introduction of a developmental element into two of them.

The introduction of episodes in subordinate keys with a departure from ostinato, to some extent, makes this form related to the rondo (see Chapter VII), however, with a significant predominance of the variational beginning. This type of variation, due to its somewhat greater dynamism, proved to be historically stable (Rimsky-Korsakov's operas).

Double variations

Occasionally there are variations on two themes, called the double. They first set out both themes, then follow in turn variations on the first of them, then on the second. However, the arrangement of the material could be freer, as exemplified by the Andante from Beethoven's Fifth Symphony: vols. 1-22 A Subject

tt. 23-49 B Theme (together with development and return to A)

50-71 A I variation

72—98 V I variation

98-123 A II variation 124-147 Thematic interlude 148-166 B II variation 167-184 A III variation (and transition) 185-205 A IV variation 206-247 Koda.

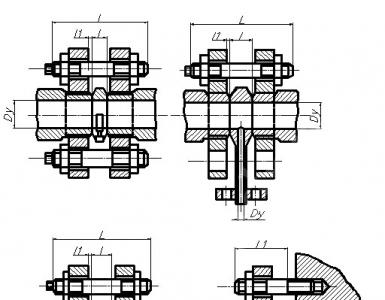

Scope of variational forms

The variational form is very often used for independent works. The most common names are: “Theme with Variations”, “Variations on a Theme ...”, “Passacaglia”, “Chaconne”; less common is "Partita" (this term usually means something else, see ch. XI) or some individual title, like "Symphonic etudes". Sometimes the name does not say anything about the variation structure or is completely absent and the variations are not even numbered (see the second parts of Beethoven's sonatas, op. 10 No. 2 and op. 57).

Variations have an independent separate structure, as part of a larger work, for example, choirs or songs in operas. Especially typical is the construction in a variational form of completely isolated parts in large cyclic, that is, many-part forms.

The inclusion of variations in a large form, as a non-independent part, is rare. An example is the Allegretto of Beethoven's seventh symphony, the plan of which is very peculiar in placing the trio among the variations, due to which, as a whole, a complex three-movement form is obtained.

Even more exceptional is the introduction of a theme with variations (in the truest sense of the term) as an episode in the middle movement of sonata form in Shostakovich's seventh symphony. A similar technique is observed in Medtner's first piano concerto.

The term basso ostinato means the continuous repetition of the same melodic turn, which is the theme of the variations, in the lower voice. These variations grew out of variations of the 16th century, reached their peak in the Baroque era (XVII - the first half of the 18th century) and were revived in the 20th century. In the Baroque era, their existence was associated with the cultivation of the bass, the doctrine of the general bass, as well as polyphonic thinking.

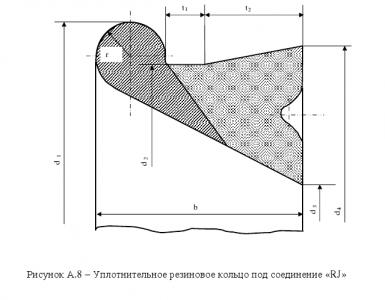

Variations on basso ostinato were associated with the genres of passacaglia and chaconne - slow pieces with a four-eight bar theme. The theme of ostinato variations is most often short, simple, and is first presented in one voice (in the passacaglia) or in many voices (in the chaconne). In the 17th-18th centuries, it has a measured movement, mostly in a minor mode, in size ¾ (in the chaconne there is an accent-syncope on the second beat), and a psychologically deep character.

Two types of themes can be distinguished: closed, which were predominantly more developed, and open, which were often built as a descending chromatic movement from the tonic to the dominant - descending, ascending, diatonic or chromatic. This intonation structure opened wide opportunities for the composer regarding harmonic and polyphonic development. Actually, the main attention is gradually shifting to this additionally composed and more expressive material in the upper voices. The ostinato theme, being repeated many times, fades into the background in perception, leaving behind a purely constructive role. One implementation of the theme in the bass is not separated from the next, and the variations go one after another without a definite end to the previous one and the beginning of the next one. In some places the limit of the new variation does not coincide with the beginning of the theme in the bass. Sometimes, in the middle of the variations, the theme can be transferred to the soprano (Passacaglia in c-moll by J.S. Bach). Along with the main theme, other themes may appear during variation (in Bach's Chaconne in d-moll, the number of themes is at least 4). The texture of the variations is adorned with expressive musical and rhetorical figures.

The tonality and structure of the theme in the chaconne and passacaglia remain unchanged; it is only allowed to change the mode to the one of the same name.

At more Variations characteristic is the combination of several of them into separate groups on the basis of the same type of variation - approximately similar melodic and rhythmic pattern of polyphonic voices, registers, and the like. Variations are located according to the principle of complication of texture or contrasting comparison of groups.

Of great formative importance is the distribution of "local" and general culminations, which unite the form.

Since the basso ostinato variations are based on a constant, as if importunate theme, they are well suited for expressing in music moods of deep reflection, focus on one thing, lack of freedom and inactivity, which are opposed by free development in the upper voices (contrast in simultaneity).

The form of variations on the ostinato bass was based on both harmonic and polyphonic principles of development. In the 20th century, many composers turned to variations on the ostinato bass: Reger, Taneyev, Hindemith, Shostakovich, Schnittke, while in the 19th century this rarely happened (the finale of the 4th symphony of Brahms).

Strict figurative (ornamental) variations

« Pieces with variations should always be based on ariettas known to the listeners. When performing such pieces, one should not deprive the audience of the pleasure of delicately singing along with the performer ”(I.P. Milkhmayer, 1797).

The main difference from variations on the ostinato bass is the homophonic basis of thinking.

Features:

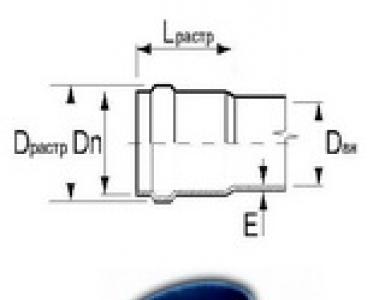

1. The theme is written in a simple two-part, less often in a simple three-part form.

2. The main method of development is textured, consisting in ornamenting the theme, splitting durations (diminution), and using figurations.

3. The form of the theme is maintained in all variations with the assumption of a slight expansion and codes.

4. The tonality is the same, but with a typical replacement for the one of the same name in the middle of the cycle or towards the end.

5. One change of tempo is allowed, closer to the final variation.

Variation of the theme is not limited to its complication. Along with this, for contrast, the simplification of the theme is also used - harmonic or textural, including through the reduction of voices (for example, instead of homophonic four-parts, polyphonic two-parts are introduced). In some cases, there is a change in time signature, although in general, variations of the classical era, while retaining the main features of the theme, also retain its meter and tempo.

The structure of the cycle of variations

There is a certain trend in the arrangement of variations:

1. Classical variations, to a greater extent than old ones, contrast in character with each other and are arranged in such a way that each subsequent one is more complex than the previous one.

2. In large variational cycles with a significant number of variations, the location is characteristic recent groups, on the basis of the same type of variation of the theme. The group of variations placed side by side is presented in approximately the same texture, due to which the composition as a whole is perceived by larger sections.

3. The placement of punchlines is of great importance for combining variations.

4. In this sense, the principle of contrast also plays a significant role. This is facilitated by the use of the tonality of the same name for some variations (comparison of major and minor). In addition, the contrast of tempos is gradually becoming normal.

5. For the overall composition of the variational cycle, the structure and features of the last two variations are of great importance. The penultimate variation often returns to the initial or close to it presentation of the topic, sometimes written in a slower movement or tempo. The last variation completes the cycle, and therefore it can use a more complex texture, change the tempo or meter, expand the structure. After it, a code can be entered.

The form of classical figurative variations has stabilized in the works of Mozart: the number of variations is more often 6, maximum 12; pre-final variation in adagio tempo, the last one - in the nature of the finale of the instrumental cycle, with a change in tempo, meter, genre. Beethoven's number of variations changed from 4 to 32.

VARIATIONS(lat. variatio, “change”) , one of the methods of composing technique, as well as the genre instrumental music.

Variation is one of the fundamental principles of musical composition. In variations, the main musical idea undergoes development and changes: it is re-stated with changes in texture, mode, tonality, harmony, the ratio of contrapuntal voices, timbre (instrumentation), etc.

In each variation, not only one component can change (for example, texture, harmony, etc.), but also a number of components in the aggregate. Following one after another, the variations form a variational cycle, but in a broader form they can be interspersed with some other thematic material, then the so-called. dispersed variational cycle. Variations can also be an independent instrumental form, which can be easily represented in the form of the following scheme: A (theme) - A1 - A2 - A3 - A4 - A5, etc. For example, independent piano variations on Diabelli's waltz, op. 120 by Beethoven, and as part of a larger form or cycle - for example, the slow movement from the quartet, op. 76, No. 3 by J. Haydn.

Works of this genre are often called "theme with variations" or "variations on a theme". The theme can be original, author's (for example, symphonic variations Enigma Elgar) or borrowed (for example, I. Brahms' piano variations on a theme by Haydn).

The means of varying the theme are diverse, among them are melodic variation, harmonic variation, rhythmic variation, tempo changes, changes in tonality or modal mood, texture variation (polyphony, homophony).

The variation form is of folk origin. Its origins go back to those samples of folk song and instrumental music, where the main melody was modified during couplet repetitions. Especially favorable for the formation of variations is the choral song, in which, despite the similarity of the main tune, there are constant changes in other voices of the choral texture. Such forms of variation are characteristic of polyphonic cultures.

In Western European music, the variational technique began to take shape among composers who wrote in a strict contrapuntal style (cantus firmus). The theme with variations in the modern sense of this form arose around the 16th century, when passacaglia and chaconnes appeared. J. Frescobaldi, G. Purcell, A. Vivaldi, J. S. Bach, G. F. Handel, F. Couperin widely used this form.

The main milestones in the history of variations are variations on a given melodic line, the so-called. cantus firmus in the vocal sacred music of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance; variations for lute and keyboard instruments in Spanish and English music of the late Renaissance; clavier works by the Italian composer J. Frescobaldi and the Dutchman J. Sweelinck in the late 16th and early 17th centuries; the suite of variations is one of the early forms of the dance suite; English ground form - variations on a short melody repeated in the bass voice; the chaconne and passacaglia are forms similar to the ground, with the difference that the repetitive voice in them is not necessarily bass (the chaconne and passacaglia are widely represented in the works of Bach and Handel). Among the most famous variation cycles of the early 18th century. – Variations by A. Corelli on the theme of La Folia and Goldberg variations J.S. Bach. Probably the most brilliant period in the history of variations is the era of mature classics, i.e. late 18th century (works by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven); as a method of variation today remains an important component of instrumental music.

The term "variations" in music denotes such changes in the melody in the process of unfolding the composition, in which its recognizability is preserved. The one-root word is "option". That is something similar, but still a little different. So it is in music.

Constant update

A variation of the melody can be compared to We easily recognize our friends and relatives, no matter what emotional experiences they may experience. Their faces change, expressing anger, joy or resentment. But personality traits while being preserved.

What are variations? In music, this term means specific form works. The play begins with the sound of a melody. As a rule, it is simple and easy to remember. Such a melody is called a variation theme. She is very bright, beautiful and expressive. Often the theme is a popular folk song.

Variations in music reveal the skill of the composer. A simple and popular theme is followed by a chain of changes to it. They usually retain the tonality and harmony of the main melody. They are called variations. The task of the composer is to decorate and diversify the theme with the help of a number of special methods, sometimes quite sophisticated. A piece consisting of a simple melody and its changes following one after another is called variations. How did this structure come about?

A bit of history: the origins of the form

Often musicians and art lovers wonder what variations are. The origins of this form lie in ancient dances. Citizens and peasants, nobles and kings - everyone loved to move in sync with the sound of musical instruments. Dancing, they performed the same actions to a constantly repeating chant. However, a simple and unpretentious song that sounds without the slightest change got bored quickly. Therefore, the musicians began to introduce various colors and shades into the melody.

Let's find out what variations are. To do this, turn to the history of art. Variations first made their way into professional music in the 18th century. Composers began to write plays in this form, not to accompany dances, but to listen. Variations were part of sonatas or symphonies. In the 18th century, this structure of a piece of music was very popular. Variations of this period are quite simple. The rhythm of the theme and its texture changed (for example, new echoes were added). Most often, variations sounded in major. But there was definitely one minor. The gentle and sad character made it the most striking fragment of the cycle.

New Variation Options

People, worldviews, eras have changed. The turbulent 19th century came - the time of revolutions and romantic heroes. The variations in music also turned out to be different. The theme and its changes became strikingly different. Composers achieved this through so-called genre modifications. For example, in the first variation, the theme sounded like a cheerful polka, and in the second it sounded like a solemn march. The composer could give the melody the features of a bravura waltz or a swift tarantella. In the 19th century, variations on two themes appear. First, one melody sounds with a chain of changes. Then it is replaced by a new theme and variants. So composers brought original features to this ancient structure.

Musicians of the 20th century offered their answer to the question of what variations are. They used this form to show complex tragic situations. For example, in Dmitri Shostakovich's Eighth Symphony, variations serve to reveal the image of universal evil. The composer changes the initial theme in such a way that it turns into a seething, unbridled element. This process is connected with filigree work on modification of all musical parameters.

Types and varieties

Composers often write variations on a theme that belongs to another author. This happens quite often. An example is Sergei Rachmaninov's Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. This piece is written in variational form. The theme here is the melody of Paganini's famous violin caprice.

A special variation of this popular musical form is the so-called basso ostinato variations. In this case, the theme sounds in a lower voice. A constantly repeated melody in the bass is hard to remember. Often the listener does not isolate it from the general flow at all. Therefore, such a theme at the beginning of a composition usually sounds monophonic or is duplicated in an octave.

Variations on sustained bass are often found in Johann Sebastian Bach's organ works. The monophonic theme is played on the foot keyboard. Over time, variations on the basso ostinato became a symbol of the sublime art of the Baroque. It is with this semantic context that the use of this form in the music of subsequent eras is associated. The finale of the fourth symphony by Johannes Brahms is solved in the form of variations on a sustained bass. This work is a masterpiece of world culture.

Figurative potential and nuances of meaning

Examples of variation can also be found in Russian music. One of the most famous examples of this form is the chorus of Persian girls from Mikhail Glinka's opera Ruslan and Lyudmila. These are variations on the same melody. The theme is an authentic oriental folk song. The composer personally recorded it with notes, listening to the singing of the bearer of the folklore tradition. In each new variation, Glinka uses an ever more varied texture, which colors the unchanging melody with new colors. The nature of the music is gentle and languid.

For everybody musical instrument variations have been created. The piano is one of the composer's main assistants. The famous classic Beethoven especially loved this instrument. He often wrote variations on simple and even banal themes. unknown authors. This made it possible for the genius to show all his skills. Beethoven transformed primitive melodies into musical masterpieces. His first composition in this form was nine variations on Dressler's march. After that, the composer wrote a lot of piano works, including sonatas and concertos. One of recent works the masters are thirty-three variations on the Diabelli waltz theme.

Modern innovations

The music of the 20th century shows a new type of this popular form. Works created in accordance with it are called variations with a theme. In such pieces, the main melody sounds not at the beginning, but at the end. The theme seems to be assembled from distant echoes, fragments and fragments scattered throughout the musical fabric. The artistic meaning of such a structure can be the search for eternal values among the surrounding bustle. Finding a lofty goal is symbolized by the theme that sounds at the end. An example is the third piano concerto. The 20th century knows many cult works written in variational form. One of them is "Bolero" by Maurice Ravel. These are variations on the same melody. With each repetition, it is performed by a new musical instrument.

from lat. variatio - change, variety

A musical form in which a theme (sometimes two or more themes) is presented repeatedly with changes in texture, mode, tonality, harmony, the ratio of contrapuntal voices, timbre (instrumentation), etc. Not only one component (for example, ., texture, harmony, etc.), but also a number of components in the aggregate. Following one after another, V. form a variational cycle, but in a broader form they can be interspersed with c.-l. other thematic. material, then the so-called. dispersed variational cycle. In both cases, the unity of the cycle is determined by the commonality of thematics arising from a single art. design, and a complete line of muses. development, dictating the use in each V. of certain methods of variation and providing a logical. the connection of the whole. V. can be as an independent product. (Tema con variazioni - theme with V.), and part of any other major instr. or wok. forms (operas, oratorios, cantatas).

V.'s form has nar. origin. Its origins go back to those samples of folk song and instr. music, where the melody changed with couplet repetitions. Particularly conducive to the formation of V. chorus. song, in which, with the identity or similarity of the main. melody, there are constant changes in the other voices of the choral texture. Such forms of variation are characteristic of developed polygols. cultures - Russian, cargo, and many others. etc. In the area of nar. instr. music variation manifested itself in paired bunks. dances, which later became the basis of dances. suites. Although the variation in Nar. music often arises improvisationally, this does not interfere with the formation of variations. cycles.

In prof. Western European music culture variant. the technique began to take shape among composers who wrote in contrapuntal. strict style. Cantus firmus was accompanied by polyphonic. voices that borrowed his intonations, but presented them in a varied form - in a decrease, increase, conversion, with a changed rhythmic. drawing, etc. A preparatory role also belongs to variational forms in lute and clavier music. Theme with V. in modern. understanding of this form arose, apparently, in the 16th century, when the passacaglia and chaconnes appeared, representing the V. on the unchanged bass (see Basso ostinato). J. Frescobaldi, G. Purcell, A. Vivaldi, J. S. Bach, G. F. Handel, F. Couperin and other composers of the 17th-18th centuries. widely used this form. At the same time, musical themes were developed on song themes borrowed from popular music (V. on the theme of the song "The Driver's Pipe" by W. Byrd) or composed by the author V. (J. S. Bach, Aria from the 30th century). This genus V. became widespread in the 2nd floor. 18th and 19th centuries in the work of J. Haydn, W. A. Mozart, L. Beethoven, F. Schubert and later composers. They created various independent products. in the form of V., often on borrowed themes, and V. was introduced into the sonata-symphony. cycles as one of the parts (in such cases, the theme was usually composed by the composer himself). Especially characteristic is the use of V. in the finals to complete the cyclic. forms (Haydn's symphony No. 31, Mozart's quartet in d-moll, K.-V. 421, Beethoven's symphonies No. 3 and No. 9, Brahms' No. 4). In concert practice 18 and 1st floor. 19th centuries V. constantly served as a form of improvisation: W. A. Mozart, L. Beethoven, N. Paganini, F. Liszt and many others. others brilliantly improvised V. on a chosen theme.

The beginnings of variation. cycles in Russian prof. music is to be found in polygoal. arrangements of melodies of the Znamenny and other chants, in which harmonization varied with couplet repetitions of the chant (late 17th - early 18th centuries). These forms left their mark on the production. partes style and choir. concert 2nd floor. 18th century (M. S. Berezovsky). In con. 18 - beg. 19th centuries a lot of V. was created on the topics of Russian. songs - for piano, for violin (I. E. Khandoshkin), etc.

In the late works of L. Beethoven and in subsequent times, new paths were identified in the development of variations. cycles. In Western Europe. V. music began to be interpreted more freely than before, their dependence on the theme decreased, genre forms appeared in V., variats. the cycle is likened to a suite. In Russian classical music, initially in wok., and later in instrumental, M. I. Glinka and his followers established a special kind of variation. cycle, in which the melody of the theme remained unchanged, while other components varied. Samples of such variation were found in the West by J. Haydn and others.

Depending on the ratio of the structure of the topic and V., there are two basic. variant type. cycles: the first, in which the topic and V. have the same structure, and the second, where the structure of the topic and V. is different. The first type should include V. on Basso ostinato, classic. V. (sometimes called strict) on song themes and V. with an unchanging melody. In strict V., in addition to structure, meter and harmonic are usually preserved. theme plan, so it is easily recognizable even with the most intense variation. In vari. In cycles of the second type (the so-called free V.), the connection of V. with the theme noticeably weakens as they unfold. Each of the V. often has its own meter and harmony. plan and reveals the features of k.-l. new genre, which affects the nature of the thematic and muses. development; the commonality with the theme is preserved thanks to the intonation. unity.

There are also deviations from these fundamentals. signs of variation. forms. Thus, in V. of the first type, the structure sometimes changes in comparison with the theme, although in terms of texture they do not go beyond the limits of this type; in vari. In cycles of the second type, structure, meter, and harmony are sometimes preserved in the first V. of the cycle and change only in subsequent ones. Based on connection diff. types and varieties of variations. cycles, the form of some products is formed. new time (final piano sonata No 2 by Shostakovich).

Composition Variations. cycles of the first type is determined by the unity of figurative content: V. reveal the arts. the possibilities of the theme and its expressive elements, as a result, it develops, versatile, but united by the nature of the muses. image. The development of V. in a cycle in some cases gives a gradual acceleration of the rhythmic. movements (Handel's Passacaglia in g-moll, Andante from Beethoven's piano sonata op. 57), in others - updating the polygonal. fabrics (Bach's aria with 30 variations, slow movement from Haydn's quartet op. 76 No 3) or the systematic development of the intonations of the theme, first freely moved, and then assembled together (1st movement of Beethoven's sonata op. 26). The latter is connected with a long tradition of finishing variats. cycle by holding the theme (da capo). Beethoven often used this technique, bringing the texture of one of the last variations (32 V. c-moll) closer to the theme or restoring the theme in the conclusion. parts of the cycle (V. on the theme of the march from the "Ruins of Athens"). The last (final) V. is usually wider in form and faster in tempo than the theme, and plays the role of a coda, which is especially necessary in independent. works written in the form of V. For contrast, Mozart introduced one V. before the finale in the tempo and character of Adagio, which contributed to a more prominent selection of the fast final V. The introduction of a mode-contrasting V. or group V. in the center of the cycle forms a tripartite structure. The emerging succession: minor - major - minor (32 V. Beethoven, finale of Brahms' symphony No. 4) or major - minor - major (sonata A-dur Mozart, K.-V. 331) enriches the content of variations. cycle and brings harmony to its form. In some variations. cycles, modal contrast is introduced 2-3 times (Beethoven's variations on a theme from the ballet "The Forest Girl"). In Mozart's cycles, the structure of V. is enriched with textural contrasts, introduced where the theme did not have them (V. in the piano sonata A-dur, K.-V. 331, in the serenade for orchestra B-dur, K.-V. 361 ). A kind of "second plan" of the form is taking shape, which is very important for the varied coloring and breadth of the general variational development. In some productions. Mozart unites V. with the continuity of harmonics. transitions (attaca), without deviating from the structure of the topic. As a result, a fluid contrast-composite form is formed within the cycle, including the V.-Adagio and finale most often located at the end of the cycle ("Je suis Lindor", "Salve tu, Domine", K.-V. 354, 398, etc.) . The introduction of Adagio and fast endings reflects the connection with the sonata cycles, their influence on the cycles of V.

The tonality of V. in the classical. music of the 18th and 19th centuries. most often the same one was kept as in the theme, and modal contrast was introduced on the basis of the common tonic, but already F. Schubert in major variations. cycles, he began to use the key of the VI low step for V., immediately following the minor, and thereby went beyond the limits of one tonic (Andante from the Trout quintet). In later authors, tonal diversity in variations. the cycles are enhanced (Brahms, V. and fugue op. 24 on the theme of Handel) or, conversely, weakened; v last case as compensation, the wealth of harmonics acts. and timbre variation ("Bolero" by Ravel).

Wok. V. with the same melody in Russian. composers also unite lit. text that presents a single narrative. In the development of such V., images sometimes arise. moments corresponding to the content of the text (Persian choir from the opera "Ruslan and Lyudmila", Varlaam's song from the opera "Boris Godunov"). Open-ended variations are also possible in the opera. cycles, if such a form is dictated by the playwright. situation (the scene in the hut "So, I have lived" from the opera "Ivan Susanin", the chorus "Oh, the trouble is coming, people" from the opera "The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh").

To vari. forms of the 1st type are also adjacent to the V.-double, which follows the theme and is limited to one of its varied presentations (rarely two). Variants. they do not form a cycle, because they do not have completeness; the take could go to take II, etc. In instr. music of the 18th century V.-double usually included in the suite, varying one or several. dances (partita h-moll Bach for violin solo), wok. in music, they arise when the couplet is repeated (Triquet's couplets from the opera "Eugene Onegin"). A V.-double can be considered two adjacent constructions, united by a common thematic structure. material (orc. introduction from the II picture of the prologue in the opera "Boris Godunov", No1 from Prokofiev's "Fleeting").

Composition Variations. cycles of the 2nd type ("free V.") are more difficult. Their origins date back to the 17th century, when the monothematic suite was formed; in some cases, dances were V. (I. Ya. Froberger, "Auf die Mayerin"). Bach in partitas - V. on choral themes - used a free presentation, fastening the stanzas of the choral melody with interludes, sometimes very wide, and this departing from the original structure of the chorale ("Sei gegrüsset, Jesu gütig", "Allein Gott in der Höhe sei Ehr", BWV 768, 771 etc.). In V. of the 2nd type, dating back to the 19th and 20th centuries, modal-tonal, genre, tempo, and metrical patterns are significantly enhanced. contrasts: almost every V. represents something new in this respect. The relative unity of the cycle is supported by the use of intonations of the title theme. From these, V. develops its own themes, which have a certain independence and ability to develop. Hence - the use in V. of a reprise two-, three-part and wider form, even if the title theme did not have it (V. op. 72 Glazunov for fp.). In rallying the form, slow V. plays an important role in the character of Adagio, Andante, nocturne, which is usually in the 2nd floor. cycle, and the final, pulling together a variety of intonations. material of the whole cycle. Often the final V. has a pompously final character (Schumann's Symphonic Etudes, the last part of the 3rd suite for orchestra and V. on Tchaikovsky's rococo theme); if V. is placed at the end of the sonata-symphony. cycle, it is possible to combine them horizontally or vertically with thematic. material of the previous movement (trio "In memory of the great artist" by Tchaikovsky, quartet No 3 by Taneyev). Some variations. the cycles in the finals have a fugue (symphonic V. op. 78 by Dvořák) or include a fugue in one of the pre-final V. (33 V. op. 120 by Beethoven, 2nd part of the Tchaikovsky trio).

Sometimes V. are written on two topics, rarely on three. In the two-dark cycle, one V. for each theme periodically alternates (Andante with Haydn's V. in f-moll for piano, Adagio from Beethoven's Symphony No. 9) or several V. (slow part of Beethoven's trio op. 70 No. 2). The last form is convenient for free variation. compositions on two themes, where V. are connected by connecting parts (Andante from Beethoven's Symphony No. 5). In the finale of Beethoven's Symphony No. 9, written in vari. form, ch. the place belongs to the first theme ("the theme of joy"), which receives a wide variation. development, including tonal variation and fugato; the second theme appears in the middle part of the finale in several options; in the general fugue reprise, the themes are counterpointed. The composition of the entire finale is thus very free.

At the Russian V.'s classics on two topics are connected with tradits. V.’s form to an unchanging melody: each of the themes can be varied, but the composition as a whole turns out to be quite free due to tonal transitions, linking constructions and counterpointing of the themes (“Kamarinskaya” by Glinka, “In Central Asia” by Borodin, a wedding ceremony from the opera “The Snow Maiden” ). Even more free is the composition in rare samples of V. on three themes: the ease of shifts and interweaving of thematics is its indispensable condition (the scene in the reserved forest from the opera The Snow Maiden).

V. of both types in sonata-symphony. prod. are used most often as a form of a slow movement (except for the above-mentioned works, see the Kreutzer Sonata and Allegretto from Beethoven's Symphony No. 7, the quartet "Girl and Death" by Schubert, Glazunov's Symphony No. 6, piano concertos - Scriabin and No. 3 by Prokofiev, Shostakovich's passacaglia from Symphony No 8 and from the Violin Concerto No 1), sometimes they are used as the 1st movement or finale (examples were mentioned above). In the variations of Mozart included integral part into the sonata cycle, either B.-Adagio is absent (sonata for violin and pianoforte Es-dur, quartet d-moll, K.-V. 481, 421), or such a cycle itself does not have a slow part (sonata for pianoforte A -dur, sonata for violin and piano A-dur, K.-V. 331, 305, etc.). V. 1st type often includes constituent element into a larger form, but then they cannot acquire completeness, and variation. the cycle remains open for transition to another thematic. section. Data in a single sequence, V. are able to contrast with other thematic. sections of a large form, concentrating the development of one muses. image. Variation range. forms depend on the arts. production ideas. So, in the middle of the 1st part of Shostakovich's Symphony No. 7, V. present a grandiose picture of the enemy invasion, the same theme and four V. in the middle of the 1st part of Myaskovsky's Symphony No. 25 draw a calm image of an epic character. From a variety of polyphonic forms, the V. cycle takes shape in the middle of the finale of Prokofiev's Concerto No 3. The image of a playful character arises in V. from the middle of the scherzo trio op. 22 Taneeva. The middle of Debussy's nocturne "Celebrations" is built on the timbre variation of the theme, which conveys the movement of a colorful carnival procession. In all such cases, the V. are drawn into a cycle, thematically contrasting with the surrounding sections of the form.

The V. form is sometimes chosen for the main or side part in the sonata allegro (Glinka's Jota of Aragon, Balakirev's Overture on the Themes of Three Russian Songs) or for the extreme parts of a complex three-part form (the 2nd part of Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade). Then V. exposure. sections are picked up in the reprise and a dispersed variation is formed. cycle, the complication of texture in Krom is systematically distributed over both its parts. Frank's "Prelude, Fugue and Variation" for organ is an example of a single variation in Reprise-B.

Distributed variant. the cycle develops as the second plan of the form, if the c.-l. the theme varies with repetition. In this regard, the rondo has especially great opportunities: the returning main. its theme has long been an object of variation (the finale of Beethoven's sonata op. 24 for violin and piano: there are two V. on the main theme in the reprise). In a complex three-part form, the same possibilities for the formation of a dispersed variation. cycles are opened by varying the initial theme - the period (Dvorak - the middle of the 3rd part of the quartet, op. 96). The return of the theme is able to emphasize its importance in the developed thematic. the structure of the product, while variation, changing the texture and character of the sound, but preserving the essence of the theme, allows you to deepen its expression. meaning. So, in the trio of Tchaikovsky, the tragic. ch. the theme, returning in the 1st and 2nd parts, with the help of variation is brought to a culmination - the ultimate expression of the bitterness of loss. In Largo from Shostakovich's Symphony No. 5, the sad theme (Ob., Fl.) later, when performed at the climax (Vc), acquires an acutely dramatic character, and in the coda it sounds peaceful. The variational cycle absorbs here the main threads of the Largo concept.

Dispersed variations. cycles often have more than one theme. In the contrast of such cycles, the versatility of the arts is revealed. content. The significance of such forms in the lyric is especially great. prod. Tchaikovsky, to-rye are filled with numerous V., preserving ch. melody-theme and changing its accompaniment. Lyric. Andante Tchaikovsky differ significantly from his works, written in the form of a theme with V. Variation in them does not lead to c.-l. changes in the genre and nature of the music, however, through the variation of the lyric. the image rises to the height of the symphony. generalizations (slow movements of symphonies No. 4 and No. 5, pianoforte concerto No. 1, quartet No. 2, sonatas op. 37-bis, middle in the symphonic fantasy "Francesca da Rimini", theme of love in "The Tempest", Joanna's aria from the opera "Maid of Orleans", etc.). The formation of a dispersed variation. cycle, on the one hand, is a consequence of the variations. processes in music. form, on the other hand, relies on the clarity of the thematic. structures of products, its strict definition. But the variant method development of thematism is so wide and varied that it does not always lead to the formation of variations. cycles in direct meaning words and can be used in a very free manner.

From Ser. 19th century V. become the basis of the form of many major symphonic and concert works, deploying a broad artistic concept, sometimes with a program content. Such are Liszt's Dance of Death, Brahms' Variations on a Theme of Haydn, Franck's Symphonic Variations, R. Strauss's Don Quixote, Rakhmaninov's Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Variations on a Russian Folk Song my field "" Shebalin, "Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell" by Britten and a number of other works. In relation to them and others like them, one should talk about the synthesis of variation and development, about contrast-thematic systems. order, etc., which follows from the unique and complex art. the intention of each product.

Variation as a principle or method thematically. development is a very broad concept and includes any modified repetition that differs in any significant way from the first presentation of the topic. The theme in this case becomes a relatively independent music. a construction that provides material for variation. In this sense, it can be the first sentence of a period, a lengthy link in a sequence, an operatic leitmotif, Nar. song, etc. The essence of variation lies in the preservation of thematic. fundamentals and at the same time in the enrichment, updating of the varied construction.

There are two types of variation: a) a modified repetition of thematic. material and b) introducing new elements into it, arising from the main ones. Schematically, the first type is denoted as a + a1, the second as ab + ac. For example, below are fragments from the works of W. A. Mozart, L. Beethoven and P. I. Tchaikovsky.

In the example from Mozart's sonata, the similarity is melodic-rhythmic. drawing two constructions allows us to represent the second of them as a variation of the first; in contrast, in Beethoven's Largo, the sentences are connected only through the initial melodic. intonation, but its continuation in them is different; Tchaikovsky's Andantino uses the same method as Beethoven's Largo, but with an increase in the length of the second sentence. In all cases, the character of the theme is preserved, at the same time it is enriched from within through the development of its original intonations. The size and number of developed thematic constructions fluctuate depending on general art. the intention of the whole production.

P. I. Tchaikovsky. 4th symphony, movement II.

Variation is one of the oldest principles of development, it dominates in Nar. music and ancient forms prof. lawsuit. Variation is characteristic of Western Europe. romantic composers. schools and for Russian. classics 19 - early. 20 centuries, it permeates their "free forms" and penetrates into the forms inherited from the Viennese classics. Manifestations of variation in such cases may be different. For example, M. I. Glinka or R. Schumann build a development of sonata form from large sequential units (overture from the opera "Ruslan and Lyudmila", the first part of the quartet op. 47 by Schumann). F. Chopin conducts ch. the theme of the E-dur scherzo is in development, changing its modal and tonal presentation, but maintaining the structure, F. Schubert in the first part of the sonata B-dur (1828) forms a new theme in the development, conducts it sequentially (A-dur - H-dur) , and then builds a four-bar sentence from it, which also moves to different keys while maintaining melodic. drawing. Similar examples in music. lit-re are inexhaustible. Variation, thus, has become an integral method in the thematic. development where other form-building principles predominate, for example. sonata. In production, gravitating towards Nar. forms, it is able to capture key positions. Symphony the painting "Sadko", "Night on Bald Mountain" by Mussorgsky, "Eight Russian Folk Songs" by Lyadov, early ballets by Stravinsky can serve as confirmation of this. The importance of variation in the music of C. Debussy, M. Ravel, S. S. Prokofiev is exceptionally great. D. D. Shostakovich implements variation in a special way; for him, it is associated with the introduction of new, continuing elements into a familiar topic (type "b"). In general, wherever it is necessary to develop, continue, update a theme, using its own intonations, composers turn to variation.

Variant forms adjoin variational forms, forming a compositional and semantic unity based on variants of the theme. Variant development implies a certain independence of melodic. and tonal movement in the presence of a texture common with the theme (in the forms of variation order, on the contrary, the texture undergoes changes in the first place). The theme, together with the variants, constitutes an integral form aimed at revealing the dominant musical image. Sarabande from the 1st French suite by J.S. Bach, Polina's romance "Dear Friends" from the opera " Queen of Spades", the song of the Varangian guest from the opera "Sadko" can serve as examples of variant forms.

Variation, revealing the expressive possibilities of the theme and leading to the creation of realistic. arts. image, is fundamentally different from the variation of the series in modern dodecaphone and serial music. In this case, variation turns into a formal similarity to true variation.